Articles

Articles and Chapters

Recent Publications

What’s in a Name? Confronting Organizational Culture in the U.S. Navy

United States Naval Institute Proceedings 150, no. 10 (October 2024).

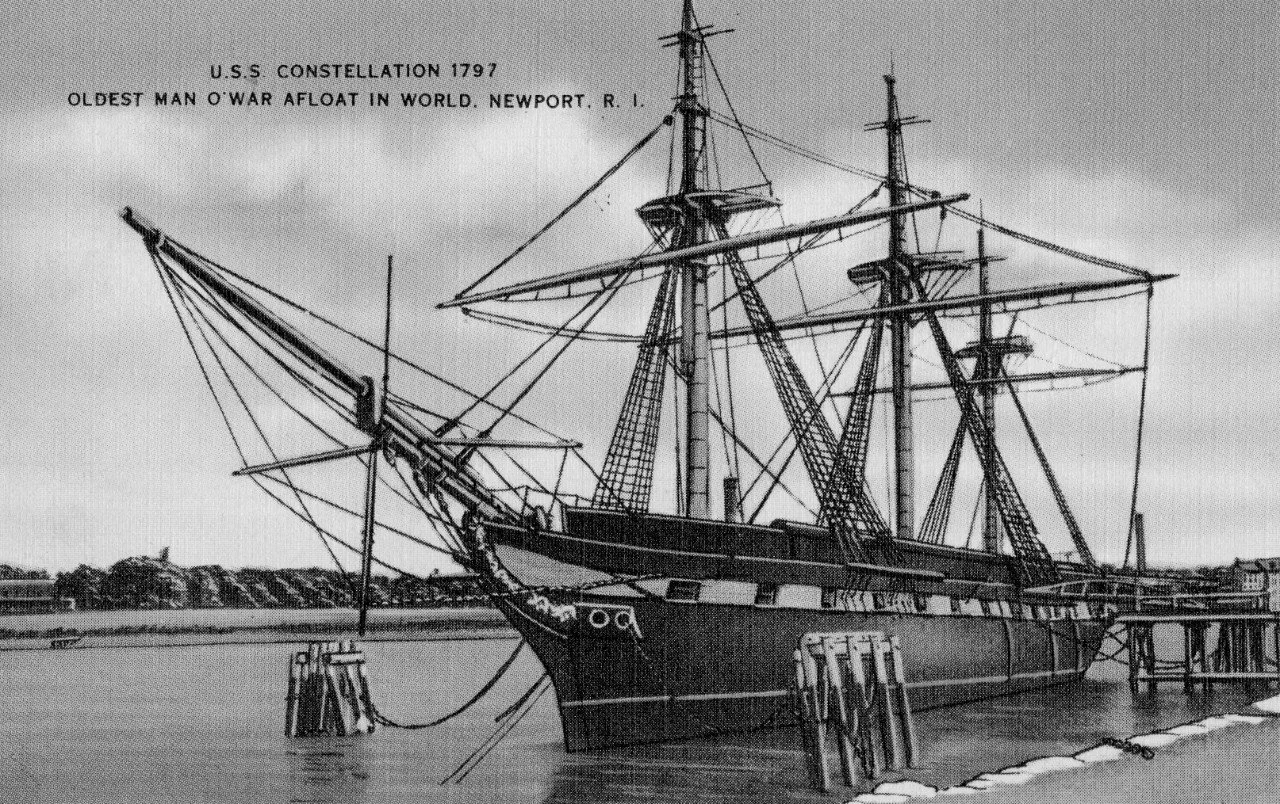

Why did the U.S. Navy mislead the public about USS Constellation? From the dismantling of the original frigate in 1852 until 1908, the navy readily admitted that the ship stationed in Newport was actually a newly-built sloop of war. But from 1909 onward, it perpetuated lies like the one visible in the image aboveExamining the history of Constellation in the U.S. Navy’s records reveals the challenges of changing organizational culture.

Navies in the West Indies During the Age of Sail

Forum. International Journal of Maritime History

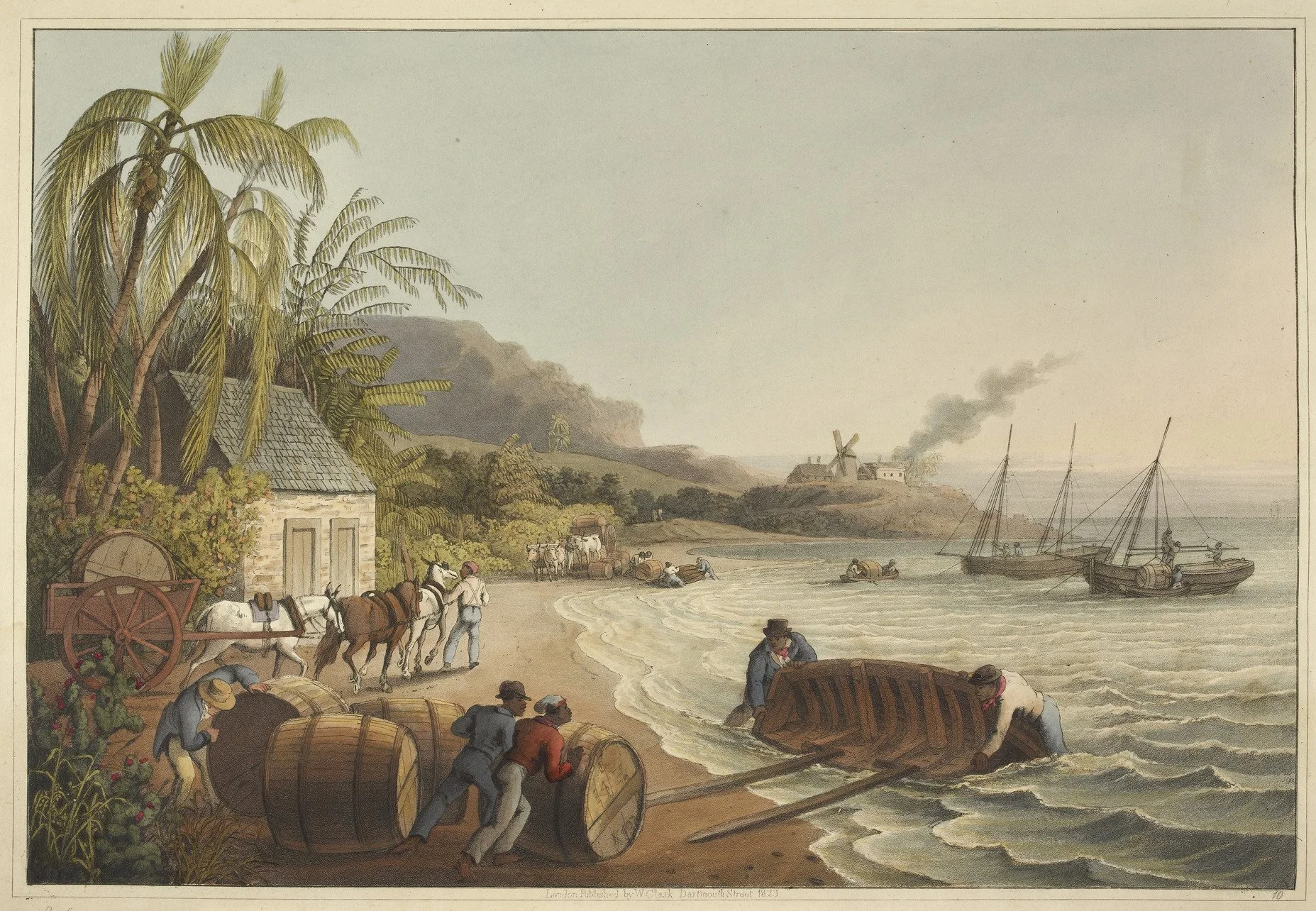

To frame this forum on navies operating in the West Indies in the age of sail, let us go back to the basics. What were the ‘ingredients’ in that bowl of sugar? And where were navies on that list? Answering these questions, it is hoped, provides background and context for the contributors’ essays, none of which deals directly with sugar, to be clear. But any historical analysis of the West Indies in this period must acknowledge how the sugar economy functioned and why it mattered.

The Monster from Elba: Napoleon’s Escape Reconsidered

the mariner’s mirror 107, no. 3 (August 2021): 265–279.

This article argues that historians have overlooked and underplayed a major British strategic error. The error was this: Napoleon’s escape from Elba in February 1815 was a preventable calamity that put the hard-won victory of the sixth coalition at risk. It had the potential to change the course of history because the allied victory at Waterloo was by no means assured. All of the allies bear some portion of the blame for Napoleon’s escape, but none more so than the British, and especially the Royal Navy, which was the only allied service capable of preventing Napoleon’s escape. Instead, Castlereagh prioritized coalition politics over Napoleon’s fate, and the navy prioritized the ongoing War of 1812 and demobilization over Mediterranean security. The British committed these blunders even though they knew that Napoleon was a flight risk, and even though the cost of reinforcing Napoleon’s guard was dwarfed by the cost of dealing with his escape.

“A Low, Surly Growl”: Returning to Britain after the Napoleonic Wars

Age of Revolutions (2023)

What was it like to be demobilized? And how did the experience of demobilization shape veterans’ interactions with the postwar world? This article illustrates the actual transition from war to peace, as seen through the eyes of soldiers returning home on transport ships, and calls attention to the importance of postwar experiences for understanding the age of revolutions.

War at Sea in the Age of Napoleon

In Oxford Bibliographies in Military History, edited by Kaushik Roy. New York: Oxford University Press, 2024.

An annotated bibliography on naval warfare in the late eighteenth century.

Other notable articles and chapters

For a complete list of publications, including book reviews, download my CV.

German Perspectives on the U-boat War, 1939-1941

Journal of military history 85, no. 2 (April 2021): 369–398.

Until the United States entered World War II, Britain’s isolation left it vulnerable to U-boats. Yet even when the campaign appeared to be going well, the German Naval War Staff worried that it was likely to be unsuccessful. The staff’s pessimism has been largely absent from the Anglophone historiography. The fundamental problem was that the Germans needed to secure a decisive result quickly, before the full weight of U.S. industrial might could be felt, but they were deploying a weapon designed for a long war. This article calls attention not only to this dilemma, but to the German awareness of it.

A Grand Tour on a Budget: Naval Officers and Intelligence Gathering in the Age of Sail

Trafalgar Chronicle, New series 9 (2024): 25–33.

Based on a conference paper, this short article explores the phenomenon of British naval officers using peacetime windows to travel in Europe and the Middle East. They did so both because gentlemen went on Grand Tours, and thus travel to the continent was associated with elevated social status, and because they could move freely in the maritime world. As an added benefit, they had opportunities to scout future enemies and even gain entrance to enemy naval facilities.

Soldiers versus Veterans: Peacemaking in Britain after Napoleon

In Soldiers in Peace-Making: The Role of the Military at the End of War, 1800–Present, ed. B.A. de Graaf, Thomas Vaisset, and Frédéric Dessberg (Bloomsbury Academic, 2023)

Tens of thousands of soldiers were discharged from the British army after Waterloo. They entered a depressed labor market, exacerbated by the eruption of Mount Tambora and subsequent “year without a summer” in 1816. In this atmosphere of unemployment, disruption, and national exhaustion, protests erupted. At the same time, more than 60,000 soldiers remained in military service after Waterloo, and they were deployed as peacekeepers and policemen around the British Isles. Soldiers made poor policemen, as they had a tendency to use their weapons sooner than the authorities usually liked. But there were few other options before the establishment of regular police forces. As a result, the postwar period was characterized by clashes between soldiers and veterans. How the two groups perceived each other, and what that says about working class and veteran identities, are questions that emerge from this research.

Sir John Orde and the Trafalgar Campaign: A Failure of Information Sharing

Naval War College Review 73, no. 2 (2020): 141-171.

Many of Sir John Orde’s contemporaries thought he was a coward, partially responsible for Nelson’s failure to track down the Combined Fleet during the summer months of the Trafalgar Campaign. Sir Julian Corbett disagreed, arguing that Orde demonstrated laudable strategic insight. Most modern historians have followed Corbett’s lead. This article challenges the Corbettian consensus to suggest a new interpretation of Orde’s actions off Cadiz.

The Naval Defence of Ireland in the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

winner of the sir julian corbett prize in modern naval history; HISTORICAL RESEARCH 92, no. 257 (2019): 568-584.

Poor weather was all that prevented the French from landing successfully at Bantry Bay in 1796—the Royal Navy was noticeably absent. This article examines the British response to this failure, with a particular focus on the under-examined early years of the Napoleonic Wars. Doing so reveals not only the continuing significance of the invasion threat and the ways in which the British countered it, but also the challenges facing British military officials—challenges that their colleagues tasked with the defense of England, Scotland, and Wales did not face. As Irish historians have noted, the first years of the Union were characterized by uncertainty about essential components of that Union: nationalism, patriotism, loyalism, and religious identity. What has not been discussed before are the ways in which those forces shaped British naval defense efforts, and vice versa. Drawing on previously unexamined sources, it connects naval defense efforts to broader questions of British and Irish history.

Particular Skills: Warrant Officers in the Royal Navy, 1775–1815

In A New Naval History, ed. quintin colville and james davey (Manchester University Press, 2018).

Warrant officers are the forgotten men of the Georgian navy. Above them, commissioned officers have received substantial historical attention, beginning with, but not limited to, the ever-increasing biographies of Nelson. Below them, the lower deck has come under increasing scrutiny, much of it focused on the question of impressment. Warrant officers of wardroom rank, on the other hand, have only been studied in fits and starts. These men—the master, the purser, the surgeon, and the chaplain—lack the glamour of commissioned officers and the political salience of impressed men on the lower deck. But the failure of the historical profession to study warrant officers should not be seen as reflecting their value to the navy and its operations. They were prominent members of every ship, and the master, purser, and surgeon had particular skills that were unique on board and essential for life at sea. They ate and in some cases berthed alongside commissioned officers in the wardroom, and saw themselves as socially and professionally comparable.

Social Background and Promotion Prospects in the Royal Navy, 1775–1815

The English Historical Review 131, no. 550 (2016): 570–95.

The professions in eighteenth-century Britain included sons of the aristocracy and sons of the middling sort. This article uses naval officers as a case-study for exploring the relationship between social status and merit. Using techniques made possible by the emergence of large quantities of digitized source material, it revises the work of Michael Lewis by describing and analyzing a database of 556 commissioned officers who served in the Royal Navy during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. Officers came from lower down the social spectrum than Lewis found, and, above a certain social threshold, there does not seem to have been any correlation between an officer’s social background and his promotion prospects. The pressures of more than two decades of war meant that senior naval officers could not afford to overlook able candidates for promotion in favour of the social elite. For naval professionals, social background mattered less than merit; however, merit retained elements of birth-right and lineage as traditionally defined in early modern Europe. The research presented here suggests that the case of naval officers differs somewhat from the existing historiography of the professions.